Rural Community Health Needs and Quality Measures

Supporting the health of a community is a complex process.

Community Health Needs and Quality Measures

Perspectives of what supports health can vary widely depending upon the culture of a community, and even depending upon the training of the practitioner or community member who is tasked with supporting their community. I have seen first hand that the healthcare culture in a metropolitan city like Tacoma, WA is different than one in rural Salida, CO. Even between hospitals, nursing homes, and telehealth facilities, the way in which practitioners interact with each other and with patients can be vastly different. It is easier to get things done in small towns, but you run the risk of making mistakes which never get noticed. The opposite side of the coin is telehealth, where you only know your coworkers by the sound of their voice when they call you with a problem you have to fix. This semi-anonymous setting allows animosity to build during stressful times. However, every task can be monitored and double checked by a number of other tele-workers, so overall quality of care is more uniform.

Another layer of complexity is introduced by the various education systems which train physicians, nurses, epidemiologists, pharmacists, and hospital administrators in their own silos. All of this, I believe, is a strength of our system. Not a weakness. Working within a hospital it is easy to see that healthcare is a team sport. We rely upon differentially trained individuals to not only be specialists, but also to overlap each others positions as a natural form of error correction. A robust system is one which cross checks itself regularly.

While varying styles, education, and cultures can help make healthcare more robust, it in turn makes coordination more difficult. To help this coordination the ACA supports or requires certain quality improvement measures to be met. These initiatives and measures are a way of testing programs, in real time, in communities across this diverse country. From rural Alaska territories to boroughs in NYC, these measures attempt to capture the underlying question what supports health in your community?

Quality Improvement Initiatives

The Center for Medicaid and CHIP services outlines Quality Improvement (QI) measures for certain improvement initiatives. Most of these initiatives are backed by grants awarded to certain states which are willing to form affinity groups. These grants mostly fund quality improvement development, data analysis, and program generation.

Initiatives listed by CMS QI include:

- Maternal and Infant Health Initiative - increase postpartum care and well-child visits, decrease low-risk c-sections, increase tobacco cessation

- Foster Care Learning Collaborative - webinars and QI support for improved access

- Infant Well-Child Visit Learning Collaborative - webinars and QI support for increased infant well-child visits

- Care of Acute and Chronic Conditions

- Asthma Learning Collaborative - webinars (2019) and QI project support (2020)

- Reducing Obesity - grant program to identify healthy eating and active living strategies, federal match for states covering USPSTF preventative services, requirements for state public awareness campaigns

- Behavioral Health Care

- Behavioral Health Learning Collaborative - support Medicaid and CHIP followup care for mental or substance use conditions

- Tobacco Cessation - supports free counselor hotlines (quitlines), mandates coverage of cessation counseling and medications

- Dental and Oral Health Care Initiative

- Oral Health Learning Collaborative - support for reduction of childhood caries, screening/diagnostic/treatment benefits for dental services, support State Oral Health Action Plans

- Preventative Care

- Childhood Screenings - supports physicals, immunizations, lab tests, health education, vision, dental, hearing, development/behavioral, and lead exposure services

- Vaccines - Vaccines for Children Program, reduced price vaccines at VFC providers, mandates adult essential health benefits coverage of vaccines

- Patient Safety - support to reduce preventable hospital-acquired conditions/complications while in facilities and during transitions

- Provider Preventable Conditions prohibition of federal payment assistance for certain health care acquired conditions commonly due to poor care (air embolisms, III/IV pressure ulcers, catheter associated UTI, surgical site infections, foreign object removal post surgery…)

- CHIPRA established safety measures - records pediatrics central line associated blood stream infections in NICU/PICU, care transition/readmission recording

- Long Term Services and Supports

- Testing Experience and Functional Tools grant program - developed the CHAPS survey for Home and Community systems (HCBS CHAPS)

- Care Transitions - technical assistance and resources to improve coordination/transitions in medical and long term services

- Medicaid Quality Grants

- (2012-2014) grants for quality care improvement collection/reporting/analysis for the Adult Core Set of quality measures

- CHIPRA quality demonstration grants

The US is a diverse landscape, especially when comparing urban and rural areas

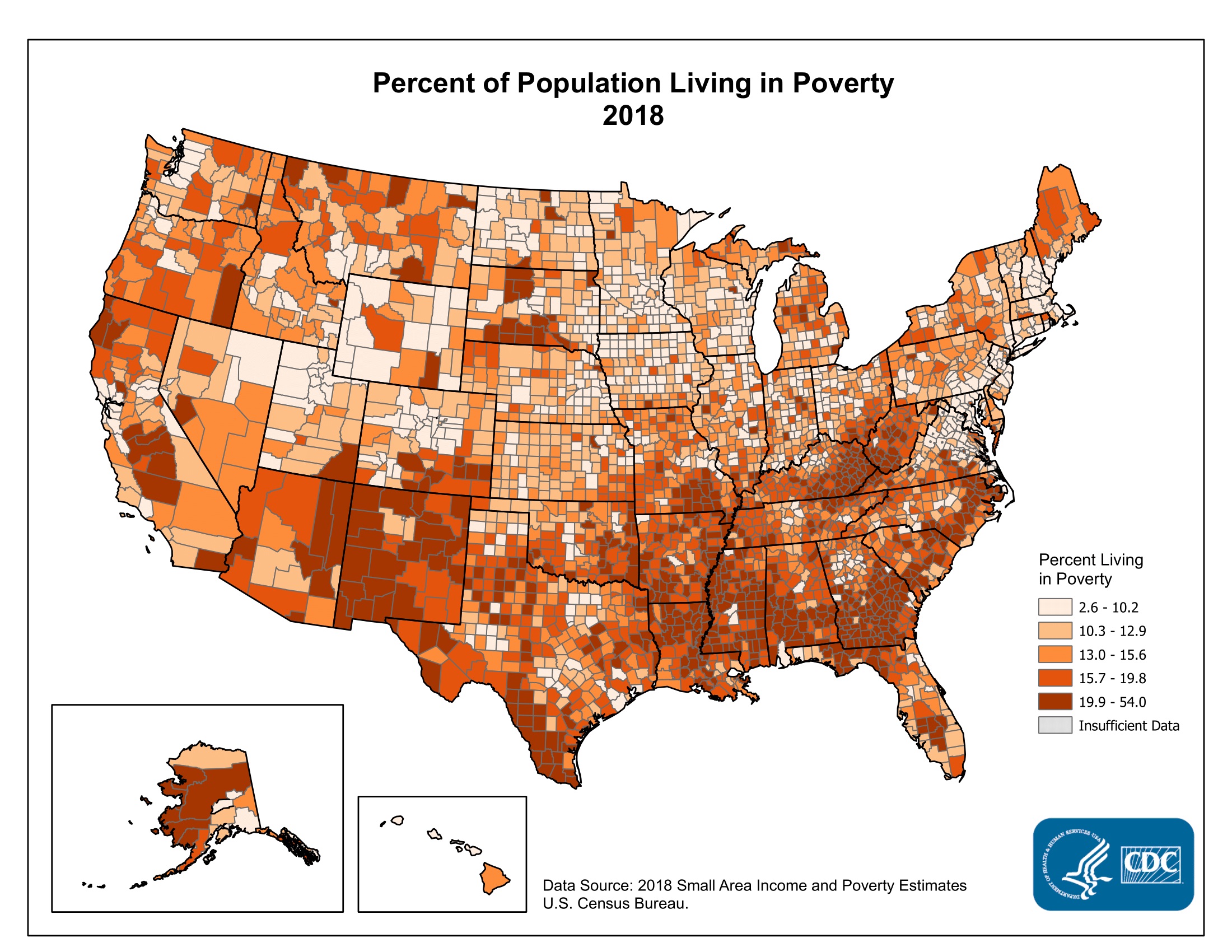

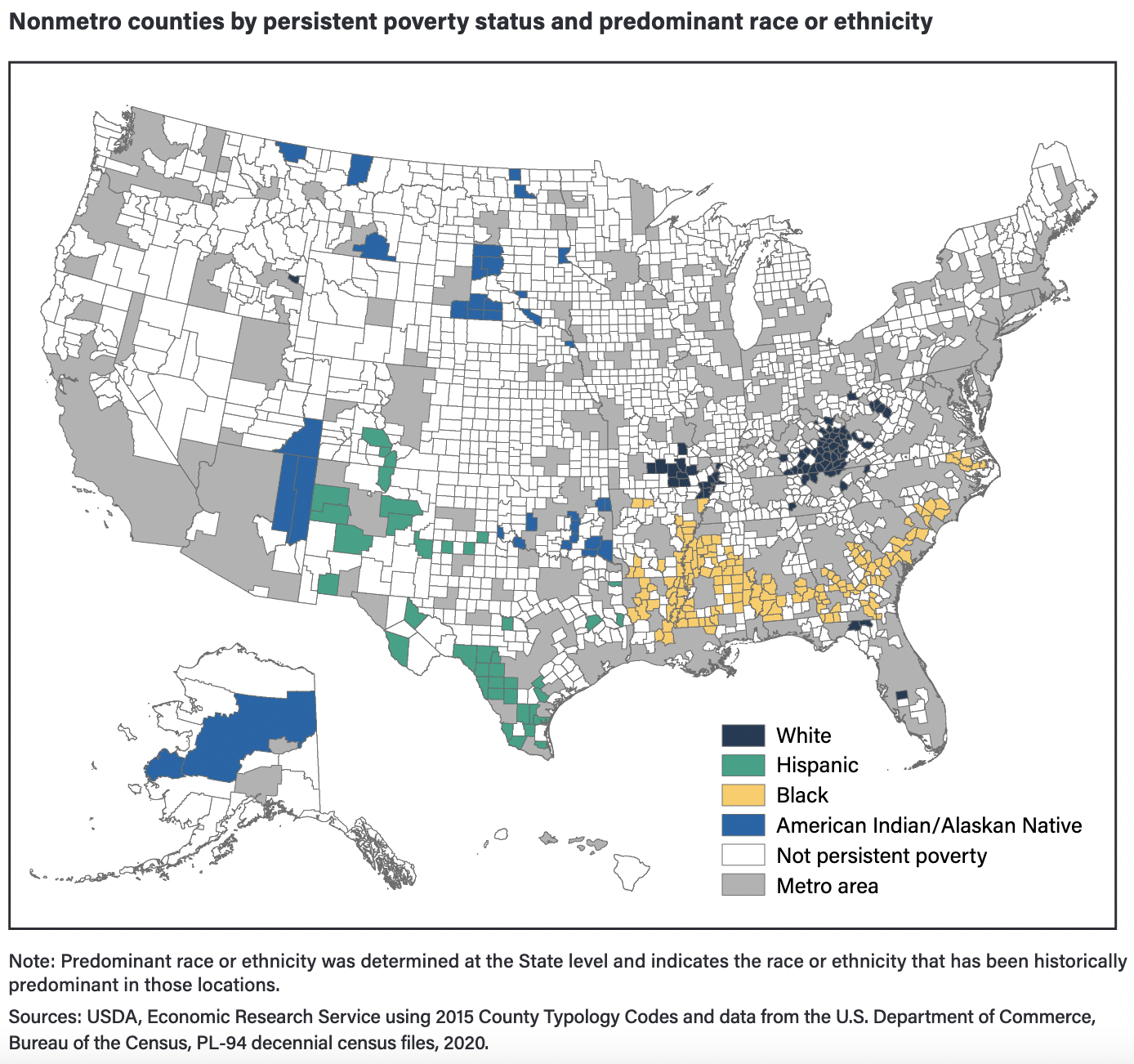

sources: 2020 US Census | CNN | 2000 US Census | 2018 US Census | US Bureau of Labor Statistics | USDA ERS | USDA ERS

-

In 2018, rural areas had a labor force participation rate of 57.6% compared to 63.7% in urban areas (Pender et al. 2019).

-

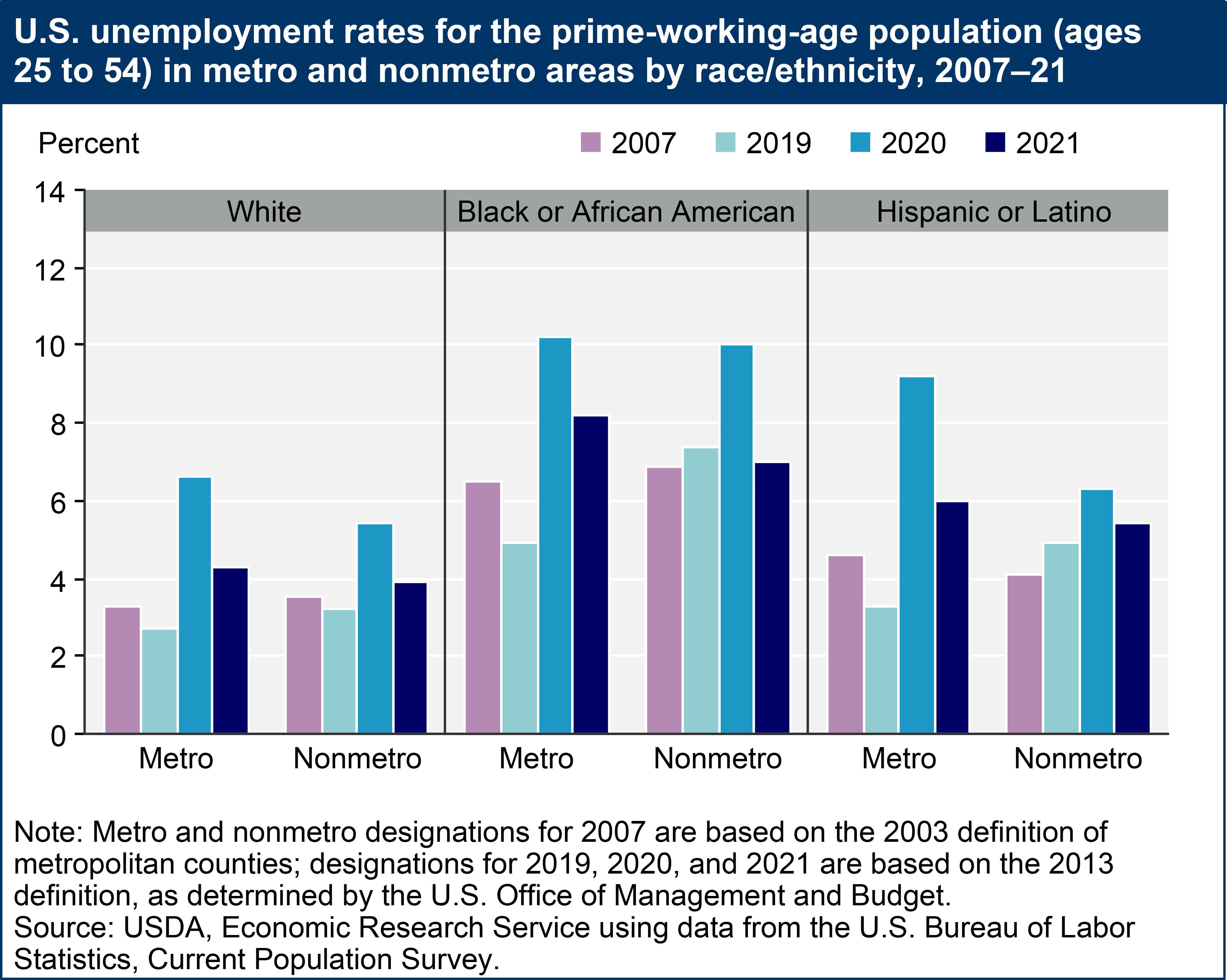

From 2007 to 2019 unemployment fell in metro counties 3.7 to 3.0 percent, but only 3.9 to 3.7 percent in nonmetro counties. When segmented by race metro areas show a pre-pandemic (2007-2019) underlying decrease in 25yo-54yo unemployment for White, Black/AA, and Hispanic/Latino; while nonmetro areas only show decreasing unemployment for White and increasing unemployment for Black/AA and Hispanic/Latino. (ERS Rural Employment and Unemployment, 2022)

-

Interestingly, the pandemic restrictions lead to a relatively lower spike in nonmetro unemployment than metro areas. (ERS Rural Employment and Unemployment, 2022). The 2021 ERS report shows a flip in unemployment with metro areas having higher unemployment than nonmetro from March 2020 until Sept 2020 and strong lingering unemployment among impoverished metro residents. Unemployment among impoverished nonmetro residents still remains high, but the post-restrictions trend is falling much faster than the metro impoverished. The metro area impoverished population appears to have a different trend than all others, and took the worst hit from the pandemic restrictions, in terms of unemployment. (ERS Rural America at a Glance, 2021 Edition, pg 7)

-

Compared to urban residents with Medicaid, more rural residents report having a disability or being limited in their ability to work due to a health problem (MACPAC 2018a).

-

The poverty rate for children in rural areas is particularly high; in 2019, 15.0% of nonmetro working age adults were poor, compared to 11.0% of working age adults living in metro areas (ERS article summary).

Health differences in rural vs urban areas

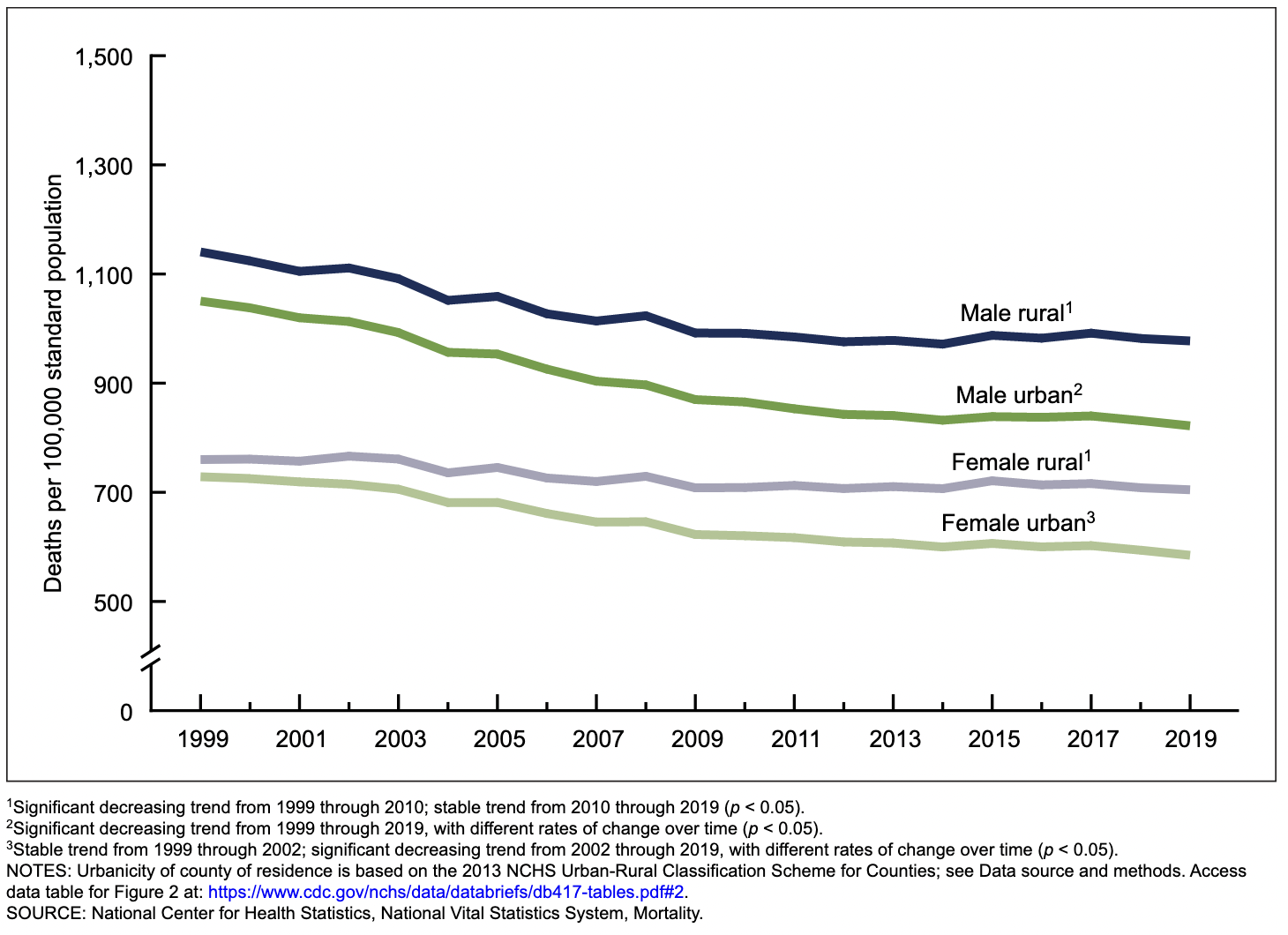

In 2019 the CDC Center for Health Statistics found worse outcomes for rural residents when measuring the top 10 death rates in the U.S. (incl. heart disease, cancer, chronic lower respiratory disease, stroke, diabetes, influenza and pneumonia, and suicide). The 2019 CDC report also notes rising disparities between rural and urban areas for heart disease, cancer, and respiratory disease.

Following a similar pattern, a series of CDC reports from 2017 found that mortality rates are higher in rural areas for the five major causes of death in the United States — heart disease, cancer, unintentional injury, chronic respiratory disease, and stroke. Rural individuals are also more likely than urban individuals to die by suicide or from a drug overdose (Mack et al. 2017, Moy et al. 2017, Ivey-Stephenson et al. 2017)

Rural challenges to health

Rural areas face considerable challenges when attempting to update and recruit their healthcare workforce. Rural students wishing to become practitioners must first leave their communities to receive education in urban or suburban schools. These environments retain workers looking for higher pay and better access to urban amenities. When speaking with my classmates and coworkers, there is sometimes a felling that rural communities are behind the times or the culture is looking backwards. People in non-urban areas may value independence over community cohesion. Rural areas may be slower to adopt new technology or practices, in part due to the costs of new programs and in part due to lack of trained or savvy individuals.

Reserch points on rural challenges to health

-

Rural residents have less access to health care services and are less likely to receive preventive services than their urban counterparts, in part because fewer health care professionals are located in rural areas (Moy et al. 2017). More than half of US health professional shortages in primary, mental, and dental care are located in rural areas (BHW 2020)

-

The supply of rural primary care providers is lower than it is in urban areas, including primary care physicians, dentists, registered nurses, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and obstetricians (RHIhub 2020). In addition, the rural health care workforce is decreasing as practitioners retire. The number of younger physicians entering rural practice has declined from 2000 to 2017 Skinner et al. 2019. These shortages are expected to worsen across the country; it is estimated that the United States will have a national shortage of between 21,400 and 55,200 primary care physicians by 2033 (AAMC 2020).

-

In an issue brief to congress by The Medicaid and Payment Access Commission they state that rural areas are in serious need of obstetrics services. More than half of all rural counties did not have hospital obstetric services in 2014 (Hung et al. 2017). Medicaid finances predominantly hospital births, leaving fewer options for women living in rural areas without access to these hospitals (MACPAC 2020, Hung et al. 2017)

-

In rural areas providers must handle the business and patient care for their facility. This is due to limited staff, finances, and lower use of Health Information Technology. Rural staff are often inexperienced in data collection because Critical Access Hospitals may optionally participate in CHS quality programs, so some do not. There is also a high variability of practice size and styles across all rural communities. (MAP Rural Health Advisory Group 2018 Report)

- The report states that rural patients are older, smoke more, have more heart disease, cancer, and strokes. They have lower incomes, higher rates of unemployment, and less education. They are also more likely to experience difficulty accessing primary, ED, dental, and mental care.

-

In a literature review of rural information needs, U of Illinois professor Josephine L. Dorsch found that rural practitioners are in need of better information sources. The review found that rural physicians are more likely to consult with eachother for information rather than doing web-based research for up to date information. Some rural physicians were unable to judge the scientific soundness of medical information on their own or with their colleges' help, specifically they had an inability to assess research methodologies and statistical results.

-

A MAP Rural Health environmental scan from May 2022 assessed the quality of health measures using grey literature and a sample of 25 Critical Access Hospitals. They found 6 of 20 current measures have potential low case-volume issues (low statistical power) when used in rural areas. To correct these issues they proposed new measures to cover patient handoffs/transitions, patient experiences of care, and readmission rates. Additional areas of improvement for rural facilities are telehealth, kidney health, equity/SDOH.

Rural programs to address health needs

“Improving Access For Rural Communities” is a criteria in the Meaningful Measures Initiative from CMS Rural Health (CMS RH) council. The CMS RH Council sets out to improve access, economic support, and “rural-relevant” measurements in rural healthcare markets. Their strategy is to apply a rural perspective for CMS programs/policies, improve access by supporting providers, increase telehealth services, empower patients in rural communities, and form networks of partnerships across disparate rural facilities.

Areas with shortages are given special designation as Health Professional Shortage Areas. These areas are the focus for access improvement, such as by building Rural Health Clinics (RHCs) and Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) to fill the gap in areas with significant shortages. In a findings brief from the NC Rural Health Research Program at UNC researchers report that there still is significant need for RHCs in the South an Midwest. In the South Atlantic census division a disproportionately large population live in counties without any RHC, FQHC, or acute care hospital.

- The South Atlantic division is made of: WV, MD, VA, NC, SC, GA, FL. As of 2022 the South Atlantic states without medicaid expansion are NC, SC, GA, FL. This leaves populations in these states particularly vulnerable to long term poor healthcare access since federal support favors medicaid expansion states.

Improvements to healthcare access come in many forms. Non-emergency medical transportation (NEMT) helps patients by paying for taxis, buses, vans, trains, or personal vehicles depending upon what is available and appropriate. Despite this assistance, in rural settings there are simply few options, if any. Many small towns only have one daily bus and one taxi service with limited range between neighboring towns. More remote areas can only be accessed by plane or boat. Remote monitoring and telemetry healthcare can offer a simple link between remote patients and providers. Tele-health nurses, physicians, heart monitors, patient sitters, and therapists (occupational/physical/speech/…) can contact anyone with broadband or satellite internet. During the COVID-19 pandemic The Consolidated Appropriations Act 2022 was passed for the Federal Public Health Emergency expansion of telemetry services and mixed services. Some telemetry services are not fully remote (mixed), having routine in person checkup requirements.

The expanded services include..

- psych diagnostic evaluations with med services

- psych visits

- end stage renal disease therapy

- eye exams

- speech/hearing therapy

- cardiac rehab

- vent management

- neuropsych evals

- gait training therapy

- orthotic/prosthetic management

- first hour of critical care for attending

- virtual home visits, including diabetes management

- alcohol/substance intervention

- off base opioid treatments (CMHS List of Telehealth Services 16 June 2022)

Even with this major improvement to access, the services may not be deliverable over slow satellite internet if a patient’s location is too remote for high speed broadband. Most software is developed with the expectation of reliable internet, even though most rural areas can not rely upon their internet. The use of emergency extension will likely lead to non-emergency use of well performing telemetry services. Before the pandemic I worked in a fully remote telemetry unit serving five hospitals around Tacoma, WA. The facility had remote sitters, remote nurses, and remote physicians. Later when working in my hometown our hospital began implementing remote sitter mobile cameras and translation services. Tele-health appears to be the simplest format to improve patient access, and it is rapidly becoming a standard of care for hospitals in urban areas too.

Conducting health needs and care quality assessments in rural settings

Statistical assessments of health needs and of healthcare quality can be challenging in rural environments. Practitioners may be inexperienced at data collection and analysis, there also may be issues with low statistical power when measuring rare conditions in small sample populations.

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement lays out the Triple Aim for improving US healthcare along the three dimensions patient experience, population health, and health care costs. Measurements which align with the triple aim include Years of potential life lost (YPLL), age standardized mortality ratios, mortality amenable to health care (death from some preventable causes before 75yo), and life expectancy by gender (predicted at birth and 65yo). Ezzati found that for some rare conditions statistically stable life expectancy predictions are not possible without a sample size of at least ten thousand observations pooled over five years. This highlights a glaring issue in rural assessments. By definition, small communities will have less than ten thousand residents. Some simple methods can use co-occurrence or family history to make better predictions, however this data is not always available.

Community Health Needs Assessment (CHNA)

The CHNA is a mandatory report for nonprofit hospitals to find their unique local community health needs every three years. The report has general requirements, but no strict measurements or format. This flexible approach can allow nonprofit hospitals to find healthcare needs that align with their particular mission. The history and current implementation of CHNAs are well laid out in a literature review by Dr. Michael Rozier on community benefits of nonprofit hospitals. Since tax exempt status was given to nonprofit hospitals in 1956 there have been a number of rulings and debates over what community benefits the hospitals need to provide. From the 80s to mid 2000s the role of nonprofit hospitals was to provide charity care, where profits were reinvested into the facility, governing boards were representative of the community, and access to care was a critical requirement. Through the early 21st century more reporting requirements were established; in 2013 the first community health needs assessment (CHNA) and community health improvement plans were conducted according to ACA requirements. Every three years, following the 2010 ACA, nonprofit hospitals must conduct a CHNA and optional CHIP to maintain tax exempt status.

CHNA components

In a 2015 review of rural CHNAs, professors from Allegheny College clearly lay out the core steps of conducting a CHNA

- establish community partnerships including

- city government

- county health and human services agencies

- local school district

- local NGOs practitioners

- community individuals

- gather information through mixed methods

- public health data review

- community forum

- key informant interviews

- community survey

- disseminate results

- description of population

- methods of data collection

- analysis results

- limitations

- biases that were noticed

CHNA requirements according to the IRS for tax exempt 501c3 nonprofit hospitals are as follows:

Community health needs assessments must be targeted at specific populations served by the healthcare facility based on that facility’s mission. The CHNA must also include a description of the specific geographic area served by the facility. Segments of the population can’t be excluded simply because they are under/uninsured, have geographic barriers to access, have language barriers, financial barriers, or because they are minorities. In short, the whole population must be considered. This even includes people who neglect or avoid healthcare.

CHNA reports are intended to assess health needs and barriers, to prevent illness, ensure adequate nutrition, and address social/behavioral/environmental factors. The reports must also be practical; they should determine the significance of health needs by estimating the burden/scope/severity/urgency of the needs. The feasibility and effectiveness of possible interventions, health disparities associated with need, and importance to community must also be considered.

The CHNA can’t just consider the diverse population served by the healthcare facility, it must also take direction from the population. The IRS would like CHNAs to be a coordinated effort by state, local, tribal, regional, government public health departments, and if relevant a State Office of Rural Health. Individuals should also weigh into the health prioritizing process, including undeserved, low-income, and minority members of the community, or groups who represent them. Additionally the IRS lists - consumer advocates, nonprofit community based organizations, academics, local government offices, local schools, healthcare providers, insurers, labor representatives.

The final CHNA report must contain:

- a community and method of determination

- the process and methods of CHNA coordination

- the methods used to collect/interpret community interests

- prioritized descriptions of health needs and methods of determining them

- health resources available in the area

- an evaluation of the previous CHNA

- an optional community health implementation plan (sometimes this is confusingly referred to as CHIP)

Facilities and health departments which have overlapping communities may duplicate portions of their report since they share the same data and community members. Shared reports can be between nonprofit, for profit, or government agencies as long as it is clear what data and roles are particular to each organization and community subset. A common method is for the county public health office to organize multiple nonprofit hospital CHNAs under one shared report. Each hospital acts as a community expert, as well as a facilitator for data collection.

A few real world CHNA examples..

Urban

The Mayo Clinic Rochester, MN is a massive multi-campus network containing two hospitals and multiple outpatient offices and specialist facilities. Services are offered to all of Olmsted county and the larger Midwest region including southerm MN, western WI, and northern ID. Mayo Clinic Rochester serves a primarily White population with a higher than average median household income and age range.

A data subgroup was made up of population health, epidemiology, and clinical community care experts from participating organizations. This subgroup used a variety of secondary data to form a list of 35 potential health indicators which were narrowed down by community and health expert opinions.

The community survey was mailed to 2000 households in Olmsted County with a 28.5% (569) response rate. There was also a convenience survey distributed to 16 sites which received 1,089 responses. In addition to the community surveys, staff from the county Human and Health Services office (250 participants) and students from U of Minnesota (190 students) helped prioritize a list of health needs. To get broader community input 18 listening sessions were conducted with specific input from youth, elderly, rural, veterans and LGBTQ groups.

Three health priorities were chosen to focus the 2019 CHNA based on their objective and subjective weights. Objective weights were decided by the data subgroup by assigning each health need a weight based on their calculated size of the at-risk population affected, health need trends in response to past investment, and the number of certain disparaged groups affected by the health need. The community, partners, and other organizations were invited to offer a subjective take on the priority health needs and urgency of needs (384 participants).

The list of top 10 community priorities were:

- Access to care

- Substance use

- Community inclusiveness

- Community mobility

- Diabetes

- Financial stress

- Homelessness

- Physical activity

- Social Connectedness

Of the top 10 priorities, the top 3 chosen were:

- Mental health

- Financial stress

- Alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs

The listening groups mostly responded with mental health needs for the community. Access to care, stigma reduction, and peer support were noted as critical needs. Youth from the RPS Student School board, the Q Club, and the LBGTQI+ Alliance all focused their discussions on mental health needs and feeling stigmatized. Overall there were discussions about lacking a sense of belonging in the community, and not feeling socially connected.

In addition to mental health needs, overall access was another topic brought up in the listening groups. Participants said they have difficulty finding or getting to facilities. Mobility impaired individuals may have more issues getting to and from appointments, or to stores when running errands. Transportation issues to facilities and in the broader area were an issue. Furthermore the lack of sidewalks and biking places were topics discussed about the built environment.

Semi-rural

Fairbanks AK, Foundation Health Partners

Fairbanks is an urban hub for rural interior Alaska. This CHNA addressed both urban and rural health issues due to its remote location. Alaska is particularly in need of health care resources since it has no in-state medical schools. Practitioner shortages and constant staff turnover are a major issue for the state.

The CHNA priorities were gathered via listening sessions, focus groups, key interviews, and community action groups. Surveys were gathered from a community health fair, partner surveys, and provider surveys. Health needs were ranked from 1-4 on their seriousness, size, disparity, specific interior Alaska need, and ability to make an impact.

The committee chose the top areas of priority:

- mental health

- youth/young adult suicide rates, depression/hopelessness, substance use, poor lifestyle choices

- senior care

- limited programs and measures, limited access

- adverse childhood experiences and trauma

- violence (ranked high by community, but less so by providers hinting at a disconnect)

- physical health

- exercise, obesity, drinking, smoking

Areas of need, which were noted but not addressed in the implementation step were

- poverty

- air/water quality

- prenatal care

- mamographies

- vaccinations

- injuries

- dental care

- accessibility

- provider burnout

- subspecialty care

- preventative care for those with intellectual disabilities

Secondary data collection was on the national and state level, with some issues collecting fine level data since Alaska is not broken up by counties. Secondary data was also collected from BlueCross BlueShield, the top insurer in AK.

According to the BlueCross BlueShield National Health Index, the top 10 conditions impacting quality of life and longevity are:

- hypertension

- major depression

- high cholesterol

- coronary artery disease

- alcohol use disorder

- type II diabetes

- psychotic disorders

- substance use disorder

- crohns disease and ulcer

- tobacco use disorder

Rural

In rural Colorado, Gunnison Valley Health is a small hospital serving a socio-economically diverse population. Nearby Gunnison, the wealthy ski resort town Crested Butte sits along side a few small low-SES towns.

Community health needs were selected based on the priority populations:

- low income

- rural residents

- children

Top needs were selected using community surveys to 23 local expert advisers. These advisers commented on the health needs of the community and data discrepancies of secondary data.

- mental health

- suicide is 7th leading cause of death in Gunnison County, female self harm and interpersonal violence, substance abuse, excessive drinking,

- affordability

Included was a long list of needs which were found but not prioritized:

- health education and preventative education

- accessibility

- primary care

- healthy lifestyles

- dental care

- cancer care

- womens' health

- chronic pain management

- accidents

- Alzheimers

- heart disease

- smoking/tobacco use

- maternal and infant care

- urgent care

- housing

- vaping

- diabetes

- kidney disease

- liver disease

- lung disease

- respiratory infections

- stroke

- obesity

- physical inactivity

- flu

The community input method had low survey responses, and free-form text responses, making this list susceptible to major bias by the 23 experts. For example, experts who responded to the community survey showed much better household mental health metrics than the rest of the community. The experts were health professionals, who tend to have medium to high paying jobs.

Secondary data was collected from county health rankings, IBM Watson Health, social vulnerability index, healthdata.org, and worldlifeexpectancy.com. Using these combined sources the following healthcare areas were found to need improvement:

- affordable care

- education on community services

- routine cholesterol screening

- female self harm and interpersonal violence related deaths

- transportation injury related deaths

The implementation plan focused on increased access to mental health services by tele health and by creating additional services or partnerships. Affordability was addressed by providing 50 free health screenings, low cost blood draws, free cancer care transportation, and mammograms for the uninsured.

CHNA areas needing improvement

In each of these CHNAs there was a comment about low sample sizes or lack of input from sub-populations of the community. Mental health and substance abuse issues tend to isolate individuals, as noted in multiple CHNAs. These are common health issues which need special focus due to their stigma and difficulty measuring or improving. While compiling this report, I noticed few CHNAs with input from youth and young adults. Since lifestyle choices are ingrained at a young age, this is an essential population to account for. The youth can also give honest insight into their family dynamics. A simple way to learn about a wider spectrum of the population could be done by reaching out to local highschool kids for their opinions of the community health needs. At that age kids are bright and often optimistic about change, it seems like an oversight to not include their efforts in every community needs assessment. Aside from their novel insight, it would emphasize their value as members of the community and may well inspire the next generation of healthcare leaders.

Across the many reports that were reviewed for this article, only some community input came from LGBTQ+ groups. The lack of gender/orientation diverse voices in CHNAs can leave these especially vulnerable people without knowledge of how to find safe healthcare, specifically in rural areas. Urban areas may advertise inclusiveness or specific support for the LGBTQ+ community. Rural areas may be culturally opposed, or at least negligent, towards advertising this support. This is an especially difficult issue to address since the practitioners' own biases are often the root of the issue. In rural areas with strong cultures, it may be impossible to find LGBTQ+ groups that can be included in the CHNA coalition. For similar reasons, minority ethnic groups are often left out of the prioritizing process. CHNAs tend to cooperate with official clubs and community groups, ones which the healthcare staff have heard of. If an ethnic groups is not English or Spanish speaking and does not have a publicly visible presence in an area, they may be completely left out.

Among different survey providers there were a range of question types and survey methodologies. While this helps hospitals customize their report, it also makes it difficult to compare reports to one another. Most hospitals used a consultancy agency to provide and administer the survey, however some rural hospitals had chosen to administer their own surveys. Since hospitals may have less experience conducting and administering surveys to the community it seems likely that the survey data on rural community needs are biased or lacking validity. In fact few of the reports I read mentioned any validation checks for their survey questions and most methodologies allowed for the CHNA commission to make community health claims without proof.

Most CHNAs attempt to gather all the relevant stakeholders, ask all the relevant survey questions, guided by all the relevant community experts, and get informed by all the relevant secondary data. The issues is, who decides what is relevant? Clearly this is an issue, since every CHNA I have reviewed has a segment mentioning certain populations of the community who did not give feedback or were not consulted. If the aim of the CHNA is to find the needs of vulnerable populations, it is the most vulnerable of the vulnerable who are being left out. Those which we don’t know to look for. We can’t find them by theorizing more, we can only find them by recruiting more different people to the search, and searching in more different ways. When choosing community experts there is an overwhelming emphasis on providers and public health officials. Some community groups may weigh into reports, but there is almost no consultation with alternative health providers like traditional healers. Even in Alaska and Colorado where Indigenous populations are recognized in CHNA reports, I did read about CHNA consultation with their traditional healthcare leaders.

On a more controversial note, people with alternative expert knowledge of common health needs are working in every local bar, head shop, and strip club in the community. Psychics, barbacks, and strippers may collectively know more about the mental health of the community than a local psychologist. Public prosecutors and defenders, along with parole officers and social service workers, will have a clear and practical insight into domestic and substance abuse in the area. To some extent the CHNA must attempt to find people at rock bottom, who have landed in the social safety net or slid past it. Well meaning physicians and epidemiologists are unlikely to have much experience, or to acknowledge their personal experience, with this side of the community. It is a shame to be ashamed of the dark or grey side of the community when the goal is to improve the health of said community. Viewing and recording the uncomfortable sides of society could possibly be accomplished with sociological or anthropological measures, as these fields tend to avoid moralizing in the same way that medicine might.

To sum up my opinion of the main areas of improvement:

- Improve outreach to small community populations; specifically youth, LGBTQ+, and ethnic minorities

- Develop and validate common methodologies and survey questions

- Expand the scope of community health experts to include opinions from people with alternative personal insight

Following up…

In a followup post I discuss some ideas around how a community can take on the full report building process, in a way that could increase ownership and trust.